Suburban Ecology: Not-so-Common Natives for your Garden

We are all now no strangers to the fact that we should be using more native plants in our landscapes. I’ve said before that the goal is to have 80% of the biomass of your landscape plants be native, and as nurseries are carrying more and more of them it is easier to do now.

The easiest ones to find in local nurseries, the ones we all know and love, include Black-eyed Susan, Cardinal flowers, Butterfly weed, and Purple coneflower (actually not a NJ native), but there are many more cool native plants I’d like to introduce you to.

Some of the best perennials for supporting the eco-system are less familiar and may be a little harder to find, but worth seeking out; Baneberry, Jack-in-the-pulpit, Turtlehead, Wild Geranium, Beebalm, Beardtongue, Solomon’s-seal and Trillium. These workhorse perennials support insects, bees and birds, with berries, seeds, pollen and nectar.

Two of my favorite local growers are Toadshade Wildflower Farm and Wild Ridge Plants. One mail order, one pick up only. These are great resources and by buying from them you can support a NJ business and the ecosystem at the same time.

Toadshade Wildflower Farm is in Frenchtown, but is mail order only. Owner Dr. Randi Eckel is an entomologist so is in a unique position to offer insights on pollinators and the plants they prefer. She is growing over 500 species of native plants in her suburban back yard. As it is not zoned for commercial use she sells mail order.

You could also arrange pick up your plants at her local hardware store in Frenchtown, which is a good idea for a larger order as shipping can get expensive. I recently ordered a few hard to find plants for a total of 28.25 and the shipping was 27.97.

If you register for one of the many lectures Dr. Randi gives for the Native Plant Society of NJ, the Frelinghuysen Arboretum or a local garden club, she generally brings a good supply along to sell. If you are up to it, Toadshade also carries seeds for even more unique native perennials, and these are all locally sourced in New Jersey and nearby Pennsylvania.

Randi says asking about her favorite underused native plant, is ‘a bit like asking a parent to name their favorite child’. But she did give me a few ideas.

Strawberry Bush and Boneset

American Strawberry Bush, (Euonymous americanus), is the native version of the invasive Burning Bush (Euonymous alatus). This stunning 5’ tall plant sometimes called Bursting-Heart, is super showy in fall with scarlet fruit capsules opening to show orange seeds inside.

Late Flowering Boneset (Eupatorium serotinum) is a 5’ tall plant covered in small white flowers from September through November. Its long narrow leaves are a beautiful gray-green color. Its a great source of nectar late in the season for bees and butterflies. Salt and deer tolerant too.

Another great pollinator plant, Flat-Topped White Aster (Doellingeria umbellata) has big clusters of white flowers with chartreuse green centers in August and September. It is the host plant for several butterflies and moths including the rare Harris’ Checkerspot. It gets up to 4’ tall.

One of my favorites, Pasture Thistle (Cirsium discolor) is just what you think, one of the thistly purple plants seen growing along roads. This genus contains many pernicious weeds but this one is a good one. Find the right spot for this, and you’ll be rewarded because this tall purple fall bloomer is the host plant for Painted Lady butterflies, is a bird and bee magnet and the seed ‘fluff’ is used by goldfinches for nesting material. Grows just about any sunny spot, but its thorny so put in in the back of the border. The thorns keep the deer at bay.

The not so subtle giant Cup Plant (Silphium perfoliatum) gets to 7’. Perfoliatum means the leaves surround the stem, in this case forming ‘cups’ that catch water. You’ll find birds drinking from this after a rain. This hefty plant needs space, but in return will give you flowers all summer long. Attracts butterflies, skippers and bees and provides seeds for birds in fall.

When mine outgrew my small garden I dug it up, split it in two. Now one is thriving at mom’s house and on at a friends in Easton.

Wild Ridge Plants in Pohatcong Township, Warren County, is owned and operated by Rachel Mackow and Jared Rosenbaum at their farm. Rachel teaches foraging and has an herbal practice. Jared is a botanist and Certified Ecological Restoration Practitioner.

Their native plant nursery is on their farm, but please make an appointment. They are an all natural, chemical free business, and source all their seeds locally. They were certified ‘River Friendly’ by North Jersey RC&D in 2018. They recognize farms that protect our shared natural resources through responsible land management.

Asked about his favorite underused native Jared said ‘The more wildflower gardens I plant and the more wild areas I restore, the more I want to include native sedges in every planting palette. Sedges are grass-like plants with long leaf blades and a mounding or vase-like habit. Underground, they do remarkable work, weaving loose soil together with their fibrous roots. Sedges are the matrix into which I want to do my plantings, to build an undisturbed soil so the wildflowers feel at home, and reduce niches for weeds to recruit. Plus they have a beautiful architecture of their own’.

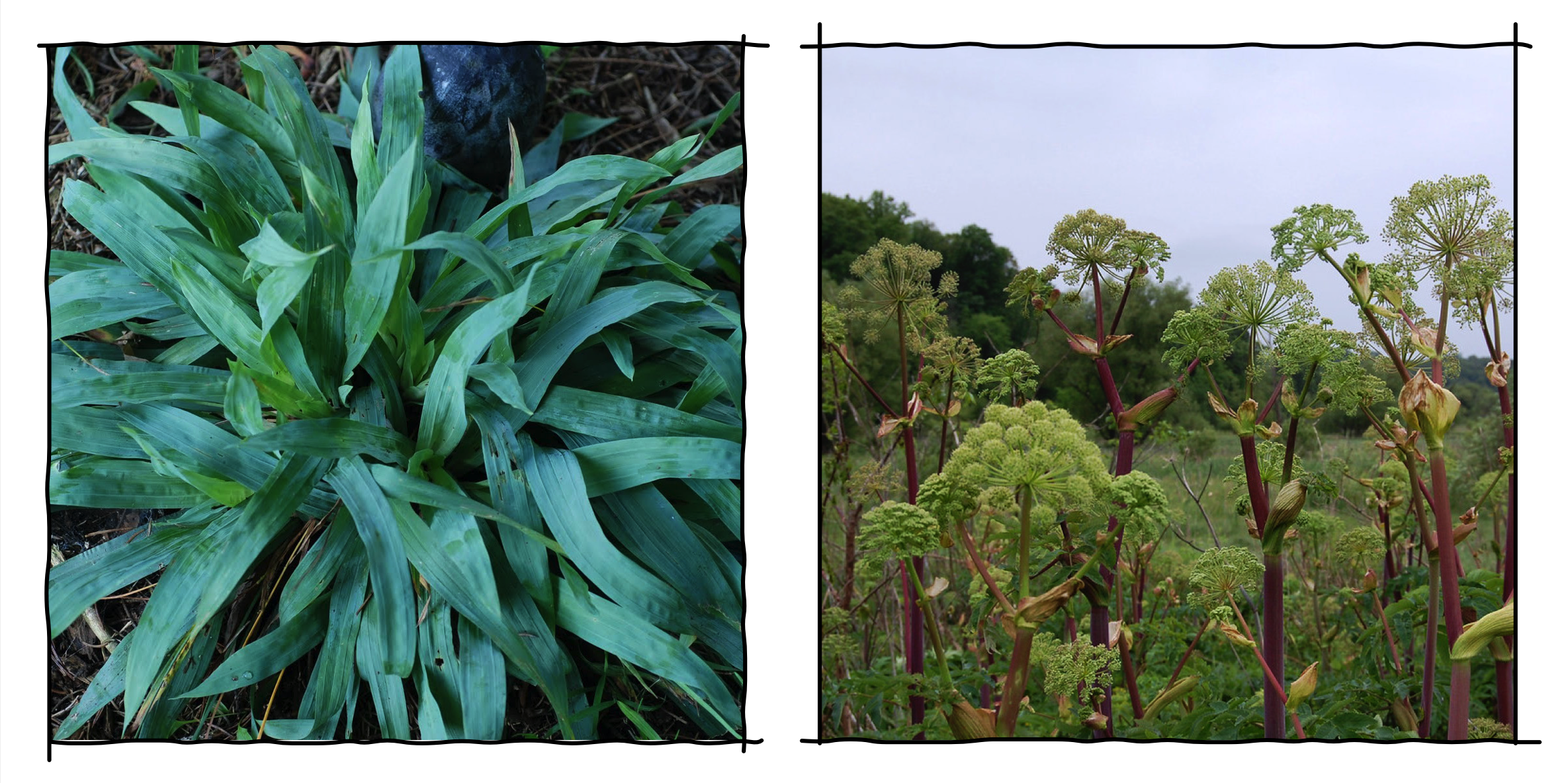

Broadleaf Sedge and Purplestem Angelica

I agree. Basically use sedges as ‘green mulch’, in-between all your other plants. There is a sedge for just about every habitat. Sunny wetlands to shaded woods. Jared favors Appalachian sedge (Carex appalachica) with fine leaves, and Rosy sedge (Carex rosea) for shaded woodlands and edges. Broadleaf sedge (Carex platphylla) and Spreading sedge (Carex laxiculmis) for their wide leaves.

A favorite of mine I spotted in the farms meadow is Purplestem Angelica (Angelica atropurpurea). A native cousin of Angelica gigas, an annual found in most nurseries. This girl gets 6’ tall and blooms in June with white balls that turn into super interesting seed heads. Great in a wet area or the back of a border with other giants like Joe Pye.

It’s hard to believe Turk’s Cap Lily (Lilium superb) is native, with its exotic looks and name. Orange flowers facing down, with their petals curled up like a…. turk’s cap, this beauty gets up to 6’ tall. Moist to wet soils, sun to shade.

This spring, plant more natives, interesting ones.

Social Distancing? Take a Closer Look Outside

Now is a great time to learn something about your own back yard, while you’re social distancing at home. Since there is no yeast to be had, instead of baking bread, meet the flora and fauna in your garden. Since fall I’ve been working on learning wildflowers, or weeds to some of you. But if you’re not into weeds, choose birds, trees, or insects.

Research has shown that when we know the name of the animals and plants we come across we tend to be more connected to them. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer says “Names are a way we humans build relationships, not only with each other but with the living world.” Not knowing “would be a little scary and disorienting–like being lost in a foreign city where you can’t read the street signs.”

The easiest way to start is just get curious. We have all the knowledge of the world in our back pockets. Think about that. With an app called Pl@ntNet I can identify a plant I’ve seen all my life but never learned the name of. Snap a photo, choose an identifying part: leaf, flower, fruit or bark, and almost instantly the common and botanical names pop up along with hundreds of other photos of it. It’s fantastic. And it works for trees too!

This week on a walk in the woods I found Virginia spring beauties (Claytonia virginica), and Woods Anemones (Anemone quinquefolia). From the road, the flowers are almost the same. It’s the leaves that give them away. Snap, snap, just to confirm my ID. The spring beauties have a grass like leaf while the anemones have a whorl of three heavily dissected leaves, a bit like poison ivy.

Left: Virginia Spring Beauties, Right: Woods Anemones

Then I come across an emerging leaf I’m not familiar with. Snap. Maianthemum canadense. I’d never recognize it from this tiny leaf; I only recognize it in flower, Canada mayflower or sometimes False Lily-of-the-Valley. With a super cool fall fruit. Now I know it’s spring look.

I’ve got a great wildflower book, two in fact, but mostly I use my phone app. Pl@ntNet is a free app, it’s part of a larger citizen science project so if you share your photos when using it, you are helping scientists, researchers, and conservationists use this crowdsourced data to look at climate change, migration patterns, and to monitor species and sensitive ecosystems. If you love this app like I do, consider making a donation to the organization.

You know the chickadees and cardinals at your backyard feeder but do you know that slate colored cutie with a white belly? Probably a Dark-eyed Junco. Another free app, Audubon Bird guide: North America, will help you identify the birds at your feeder and also let you hear their calls. You just punch in size, color, then type, and photos of possible birds keep narrowing the choices until you see the one you are looking for.

A hawk I saw recently in my back yard had a reddish belly and I assumed it was a red tail hawk. With this app I was able to identify it as a Cooper’s Hawk, and listened to its call. The app then showed me a map of recent sightings in my area. Very cool. It’s also got a built in field guide so you can study up from the comfort of your own couch. I love this because it’s so easy to use and I almost always come up with the right bird.

Last week I took a photo of an unusual bee feeding from a quince. When I got home and did some research to ID it I found out it was actually a Drone Fly. Yes, even a bee-keeper makes mistakes. The cool thing I discovered as an easy way to distinguish bees from flies is that bees have 4 wings and when landed keep them folded over their backs, while flies have only 2 wings and tend to keep them splayed out while feeding.

Bee on the left, Drone Fly on the right

I should have just used my InsectID app. A quick analysis of the photo I took and InsectID named it in seconds! Unlike the other two apps, this one costs $39.99 per year. I like it for its simplicity. Alternatively, you could get iNaturalist for free and become a citizen scientist with it.

If you are like me, and will lose that name quicker than your walk back indoors, try your hand at a sketchbook. Get a small spiral bound sketchbook to draw in. The act of drawing forces you to really study your subject and will help you remember it later. I’ve recently begun a weed sketchbook and besides the drawings I add notes to the margins.

When you’re finally back at a barbecue later this year you will impress your friends by knowing the trees in your yard, birds at your feeder and even the weeds under your feet.

Suburban Ecology: Should You Cut Down Your Ash Trees?

If you have an old, glorious ash tree in your yard, what should you do? With the emerald ash borer on the move, doing nothing is not an option. You need to either remove it or treat it.

If the tree would not cause damage if it fell, try to treat it. It will cost you about $300 every two years. But treatment over a long period is not sustainable. If you are not willing or able to make that commitment, I suggest removing the tree now.

History of Parasitic and Fungal Disease

In 1904, chestnut blight was accidentally introduced to the United States when a parasite came in from Japan with some ornamental plants. It was first detected at the Bronx Zoo. Devastatingly, by 1940, most American chestnut trees had been wiped out. Estimates put the loss at four billion trees. The chestnut was a great source of food for people and many animal species, and their populations were affected too. On the East Coast, it is estimated that one in four trees was an American chestnut. Most of us alive today never got to see these noble old trees.

Less than a generation later, in 1928, Dutch elm disease came along. It was caused by a fungi spread by elm bark beetles which arrived in the U.S. from Asia with a shipment of logs to be used as veneer for furniture. Quarantine kept it in the New York City area for thirteen years, but it eventually spread and, by 1989, we had lost 75% of these majestic trees. Imagine street lined with trees whose arching branches touched in the middle and shaded your parked car. Now imagine them suddenly gone. It was devastating. Elms we plant today are hybrids, a cross of European varieties with the remaining, most disease-resistant American specimens.

Should You Cut Down Your Ash Trees? A Possible Solution - Organic Injection Treatment

Emerald Ash Borers

Driving through the Catskills six years ago, I was saddened to see what seemed like 50 acres of trees being cut down between Rt. 28 and the Ashokan Reservoir. A sign said that trees were being removed to combat emerald ash borers. The emerald ash borer, or EAB, was first discovered in the U.S. in 2002, but it was 2014 before it got to New Jersey. It probably came from Asia on wood pallets used in shipping. This beautiful but deadly beetle will lay eggs on the ash tree’s bark. Hatched larvae then bore into the tree and feed on the tissue beneath the bark. This tissue, called xylem, is like our arteries. It moves water up and down from roots to the ends of the highest leaves. Once the xylem is destroyed, the tree is doomed.

I took comfort in the thought that New York was taking action, creating a firewall to stop the invasive beetle’s march into New Jersey. That was part of the story, but there was more. I later learned that New York had removed 4,000 trees on 200 acres, and those trees were not yet infested. New York City owns the reservoir, and had made a calculation: Cut down the trees before they become infested and ‘preserve their value’, i.e., sell the wood and make money; or wait until they inevitably become infested and get nothing. Ash wood is valuable for making baseball bats, tool handles, furniture, and flooring, but once infested with the ash borer, it is worthless and costly to remove.

The ash borer spreads by flying from tree to tree, but it’s even more likely that humans accidentally help it spread when we transport ash as firewood or lumber. In New Jersey, ash wood is now under quarantine. To slow the spread, you are not permitted move ash wood between states.

Should You Cut Down Your Ash Trees?

If you have an old, glorious ash tree in your yard, what should you do? With the emerald ash borer on the move, doing nothing is not an option. You need to either remove it or treat it.

If the tree would not cause damage if it fell, try to treat it. It will cost you about $300 every two years. But treatment over a long period is not sustainable. If you are not willing or able to make that commitment, I suggest removing the tree now. As painful as it might seem, removal is the best way to slow EAB spread. Once infected, the ash tree will die within 2-4 years. Especially if your tree is in an inhabited area, it’s important to take it down before it becomes dangerous, not only to any neighbors nearby, but also to the tree experts who have to climb into up to remove it.

If you do decide to treat your ash, consider your options carefully. Foliar spray— spraying the entire tree—is generally a bad idea. Imagine an insecticide (a poison) sprayed into the tops of a huge tree and how much of that spray ends up in the wrong places. Another option is a trunk spray which can last up to a year, but will kill all insects, not just the problematic emerald ash borer. A third choice is a soil drench, but results can be inconsistent and it will also kill beneficial insects in the soil.

The best treatment is an injection of insecticides directly to the xylem, which works much like chemo-therapy in attacking the affected tissue. A few synthetic compounds are very effective for injection. Since ash trees are not insect-pollinated, there is less danger to insects or bees. But it will kill any caterpillars living in the tree. And treatment can be toxic to birds and aquatic life, so keep it away from lakes and rivers.

An organic injection treatment is the best option. TreeAzin, similar to neem oil, interrupts larval growth and egg viability in adult EABs so that populations decline. It is injected directly into the tree, so it has much less impact on the environment. Organic Plant Care Tree Experts in Frenchtown (908-386-4346) provides injection treatments. Costs are a few hundred dollars per tree, every two years. Check out their website here for more information.

So should you cut down your ash trees or treat them? It’s up to you. For now, the scientists fear that the ash tree will suffer the same fate as the chestnuts and elms. There is little hope that we can stop the emerald ash borer and save the trees. But through awareness of the accidental harm humans cause and by taking fast, effective action, we can make the difference. Instead of becoming part of the problem, we need to start being more aware of how we treat the natural world.

What’s next? The spotted lantern fly.

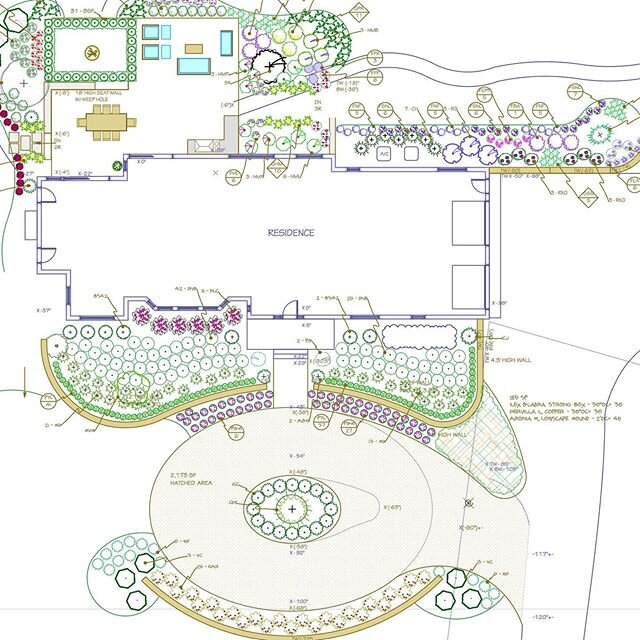

Learn more about me Carolle Huber my sustainable landscape blog and the inspiring sustainable landscapes that I design here.

Carolle

Suburban Ecology: Exotic Invasives & Our Changing Ecosystems

Twenty years ago it was a diverse forest. So full you could not see into it. So many species of trees; birch, beach, oak, ash and tulip trees. The understory was also full with viburnum, chokeberry, witch hazel and azaleas. Today most of the native understory has been eaten by an out of control deer population, and in its place has grown what we call exotic invasive’s.

I walk my dog in the woods near our home every morning. I love seeing ‘my’ Belted Kingfisher dive for breakfast in the summer and funny looking Buffleheads too. And several times a year I’m privileged to see a Bald Eagle, gliding past me over the lake. Seeing nature like this is hopeful, but I am at the same time alarmed to see the degradation of the woods on the other side of the trail.

Twenty years ago it was a diverse forest. So full you could not see into it. So many species of trees; birch, beach, oak, ash and tulip trees. The understory was also full with viburnum, chokeberry, witch hazel and azaleas. Today most of the native understory has been eaten by an out of control deer population, and in its place has grown what we call exotic invasive’s.

What To Plant Instead Of Exotic Invasives

Exotic Invasives

Japanese Barberry, Japanese Knotweed and Burning Bush, from Asia. Believe it or not, these were all brought here intentionally as ornamental plants for use in our gardens, back in the 1800’s. Even then, while they might have escaped into our woods, they did not thrive or survive. There was too much competition from our native plants. What happened? Deer.

Deer & The Importance Of Planting Native Species

People assume we caused the deer problem by developing the woods where they lived, thus reducing their habitats and forcing them into suburbia. The truth is, all that development has been great for the deer. They thrive on it. They live on the edges of the forests, and by carving out the forests to build homes, we have created many more ‘edges’. Then we landscaped our yards with their favorite foods. Some areas in New Jersey have as many as 100 deer per square mile, while scientists tell us ten per square mile is all the woods can sustain.

Deer prefer native plants over exotic ones because they co-evolved together over thousands of years, it’s what they are used to. When we had a normal deer population, the native plants were never decimated. Now, with huge populations of deer, most of the native plants are gone, leaving open areas for the exotics to exploit.

Some of our forests have passed the tipping point. There are no new trees growing to replace all the old ones that are aging out or we’ve lost in recent storms. They get eaten by deer before they are tall enough to survive. The native plant communities have been destroyed, and with their disappearance, the rest of the ecosystem is changing too. The insect populations that depend on the native shrubs disappear. The birds and rodents that survived on these insects move on. The hope is that these creatures will adapt to the new ‘normal’ but the data is not good.

Other Problems With Exotic Invasives

Two of the worst exotic invasive are Japanese Barberry and Burning Bush. Exotic, because they come from a far away country. Invasive because they spread rapidly. They have berries that birds eat in the fall. The seeds get pooped out as the birds are flying, and they germinate everywhere.

As destructive as these plants are, they are still staples in our nurseries. They have been banned from sale in most Northeast states but not NJ. They have been talking about it for years but have not made a move yet. Why? The nursery trade likes to give us what we ask for, instead of educating us on the detrimental effects of these plants.

Nurseries sell Japanese barberry because it has great red color and the deer don’t eat it, we love burning bush for its brilliant fall color, you see it in mass in corporate parking lots.

What To Plant Instead of Exotic Invasives: The Native Alternatives

Below are some worst offenders and my favorite native alternatives. These will also become habitat and food for important pollinators, small mammals and birds. And it would be worthless if they were not also on my deer ‘resistant’ list.

What To Plant Instead of Exotic Invasives :

Replace Barberry with Virginia Sweetspire, 3’ high great color, and flowers.

Replace Spirea with Ninebark. There are so many different ones, you can pick the best for the size and color you want.

Replace Norway Maple with White Oak. This is the number one best tree to support wildlife.

Replace Callery Pear with Redbud. Early spring flowers and beautiful shape.

Replace Butterfly Bush with New Jersey Tea. Least deer resistant on my list, so use accordingly. Worth trying for its summer-blooming flowers. Dry site tolerant.

Replace Burning Bush with Chokeberry or Fragrant Sumac. Great fall color, one tall one small.

Replace Miscanthus Grass with Switch Grass. So many varieties to choose from.

Replace Privet with an Arrowwood Viburnum or American Holly hedge.

Replace Forsythia with Spicebush, and look for Spicebush Swallowtails in your garden

It is simple, you would not ingest a dangerous substance, or feed it to your family. Don’t plant anything on your States Exotic Invasive Plant List.

I hope you have found this post useful and found some great native alternatives to plant instead of exotic invasives.

Learn more about me Carolle Huber my sustainable landscape blog and the inspiring sustainable landscapes that I design here.

Carolle

Suburban Ecology : A New Year's Resolution for a Healthier Planet

Now is the time to think about increasing the biodiversity of your suburban lot to support the vitality of Nature in your own corner of the world. Residential landscapes occupy almost one-fifth of the entire United States, so how we manage our yards has a large effect on the health of our planet.

Now is the time to think about increasing the biodiversity of your suburban lot to support the vitality of Nature in your own corner of the world. Residential landscapes occupy almost one-fifth of the entire United States, so how we manage our yards has a large effect on the health of our planet. What can you do this year to make your own plot friendlier to our small friends who want to thrive there? I’ve got a few ideas and resolutions for a healthier planet. Don’t feel overwhelmed; pick out 3 from my list below and make 2020 your year to make a difference in the health of the Earth.

Resolutions for a Healthier Planet

1- Have A Landscape

No kidding. No matter the size of your property or terrace, have some plants other than grass. Plants have many benefits. They absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen, they shade and cool our neighborhoods, and they reduce dust, filter water, and prevent erosion. If you have no yard, plant in pots.

2- Get A Compost Bin

Whether you build one or buy one, start composting your food waste. It’s great for your soil and conserves landfill space. Once it is ready, use it as mulch, soil amendment or organic fertilizer for your plants. Chop your scraps up for rapid composting. Match your food scraps 1 for 1 with dry brown stuff like leaves, sawdust or newspaper. When its done it should smell earthy and sweet.

3- Conserve Water

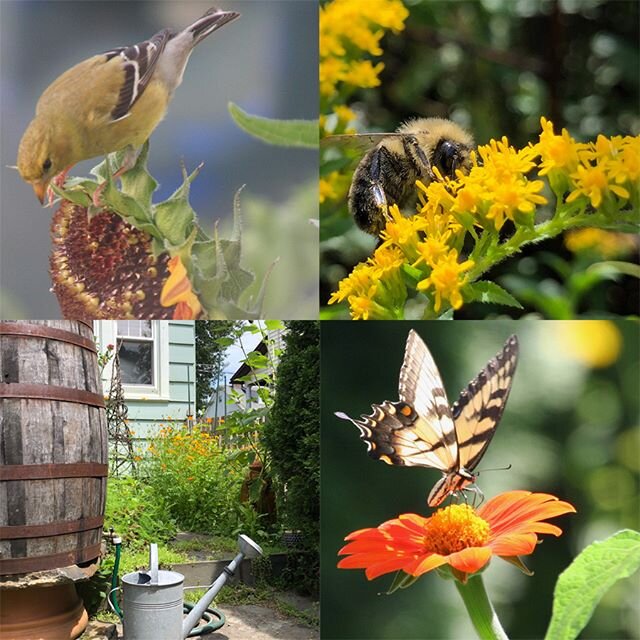

Install a rain barrel or two. Use this water for potted plants or landscape beds. You can fill up watering cans, or run a soaker hose from its spout into your landscaped beds. Water is a resource to use carefully. For each inch of rain collected from a 500 sf roof area, you can collect 300 gallons of water! I’m adding a second on this year, the first one has been so successful. I am partial to wood whiskey barrels.

If you have an irrigation system, inspect it regularly to see that heads are irrigating the landscape and not the driveway. Install a rainfall sensor that will shut the system down if it rains.

Resolution for a Healthier Planet - Wood whiskey barrel to collect rain water for the yard.

4- Create A Habitat For Wildlife

A great resolution for a healthier yard is adding plants to mimic wild areas. Layer shade trees, small trees, shrubs, perennials and ground covers that are attractive to pollinators. Here, birds can find food, shelter, and nesting sites. A birdbath helps too. I got a bird bath coil this winter to keep the water from freezing. It turns off when the temp is above freezing and costs just pennies a day.

5- Do Better Lawn Care

Switch to organic fertilizers for your lawn. Use a mulch mower and leave grass clippings on the lawn; they supply needed nutrients and help keep weeds at bay. Mow high and frequently, and never cut off more than ⅓ of the grass blade. Mowing high helps prevent weeds and crabgrass and encourages deep roots, which helps on hot summer days.

6- Hang A Bird Feeder

Two-thirds of North America's birds are at risk of extinction due to climate change. Too many suburban landscapes are over-maintained; plants get cut back in fall and removed, along with all their seeds, and leaves are blown away, taking with them all the insects that might have overwintered there. Planting the right plants to provide food for birds in spring, summer and fall, along with supplemental feeding in winter helps a lot, especially now that our winters last longer. Make sure to clean feeders thoroughly a few times throughout the winter, so you don’t help spread viruses. I hang suet for woodpeckers, and feed only sunflower seeds to greatly reduce wasted seed. If you don’t like the seed hull mess, try the shelled seeds. They are more expensive, so I switch to them late winter, when I am actively in my yard again and don't want the mess.

Planting the right plants to provide food for birds in spring, summer and fall -

A New Year's Resolution for a Healthier Planet

7- Leave The Leaves

In fall, mow over fallen leaves and leave them on your lawn or rake them into your landscape beds as winter mulch. As they deteriorate, they will improve your soil and provide nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium without expensive chemical fertilizers. They also serve as winter insect habitat, helping declining bug populations survive. If you have extra leaves, add them to your compost bin.

8- Install A Bat House

Bat numbers are diminishing because of habitat loss and disease but a bat house provides a safe place for these under-appreciated winged rodents to roost and raise their young. And you want them in your yard because they eat thousands of insects each night, so goodbye mosquitos! And they are also pollinators on the night shift. My husband Max made me one out of scrap lumber from pallets, which are usually available for free and the wood is untreated. Perfect.

9- Sign Up For A Community Garden Plot

Grow organic vegetables to feed your family, relieve stress, and rub shoulders with the diverse people that are your community. Add your name to the wait list for Grow It Green Morristown’s Early Street Community Garden and start planning your garden now.

10- Learn Weeds

I have been learning to identify weeds this year and still have a long way to go. But it has helped me to know which weeds or wildflowers are native, and which are not; which ones I pull and what I leave alone for the native insects to enjoy. A great site is Rutgers NJ Weed Gallery. My favorite phone app is PlantNet.

11- Rethink All That Lawn

Get rid of some of your lawn. Lawn uses a lot of resources, water and fertilizer. Do you use all of your lawn, or could some of it be put to better use as a vegetable or pollinator garden?

New Year's Resolutions for a Healthier Planet - What will you do this year? Let me know!

Learn more about me Carolle Huber and the inspiring sustainable landscapes that I design here.

Carolle

Trail Maintenance In The Catskills

I’m clearing and cutting in the woods, doing trail maintenance behind my house in the Catskills. Some shoots in the path are three feet high which tells you how long it’s been since I’ve done this. Beech trees grow up from the roots that extend across the path, and some of the original trees may have already died. This is the way beeches prolong their life. They find a patch of sun and the meristem (basically the “stem cells” of plants), dormant for many years can shoot up and create a whole new tree. Or not a new tree but the same tree in a different location. When I’m with 12-year-olds, I call them, “Sons of beeches.” They’ll never forget, and maybe think plants aren’t so boring after all.

I’m clearing and cutting in the woods, doing trail maintenance behind my house in the Catskills. Some shoots in the path are three feet high which tells you how long it’s been since I’ve done this.

Tools For Trail Maintenance In The Catskills

Beech trees grow up from the roots that extend across the path, and some of the original trees may have already died. This is the way beeches prolong their life. They find a patch of sun and the meristem (basically the “stem cells” of plants), dormant for many years can shoot up and create a whole new tree. Or not a new tree but the same tree in a different location. When I’m with 12-year-olds, I call them, “Sons of beeches.” They’ll never forget, and maybe think plants aren’t so boring after all.

I have friends, Patti and Bill, who maintain the nearby Rochester Trail. But I am doing this for purely a selfish reason: so I can get to the river easier.

Different Species In The Catskills

My dad, son of an English professor, would know the names of all these trees. But after cutting away three downed branches, he would sit down to muse about the place or its history. My mom, daughter of farmers, would not know or care for the names of these plants, but would love to see all the green moss popping up through the leaves and hear the grouse drumming in the distance. She could do this type of work for eight hours without stopping.

And then there is me, I guess a little of both. If I don’t know a plant’s name, I take a picture with my phone so I can identify it later (PlantNet is my current favorite App). I love botanical names. I know the Latin names of all the plants for sale in nurseries. I love what the names tell us about the plants. Take Witch-hazel: Hamamelis virginiana. The first word (or genus) comes from the Latin hama, meaning “at the same time,” and melon, meaning fruit. This small tree fruits and flowers at the same time. And the species virginiana tells us it’s from Virginia—in other words, the east coast.

I also like the fact that I can spot from a distance the ‘hops’ of a hornbeam even with all the leaves gone, and the catkins of a birch, and the seed capsules of Witch-hazels which have just finished blooming. But I’m not so good with the smaller local plants. I see moss as moss and mushrooms as mushrooms, but I’m learning to be more curious and have started to learn their names, too. Mushrooms like fan-shaped Turkey Tails on fallen logs, brittle Russula or a Bolete under an oak.

I can keep at this work for hours, too, like Mom, stripping off layers of clothes as I go.

Those of us who like this type of work wear layers as we are told to do in the cold, but not for the reason you think. It’s not to keep us warm, but to take them off. We know that in 40° F weather, after half an hour we’ll take off the first layer, another half hour and the second one is off, and so on.

Being Outside - Trail Maintenance In The Catskills

It’s hard work and it’s easy work, too. Being outside, I’m maybe the only person within half a mile. Me and my dog Garçon. Looking up at the sky, the trees forming a cathedral over me. It’s like going to church and the gym at the same time. Though it’s Thursday, I’d call this Sunday Service.

Some would question why clean I up the woods, since nature made it that way. I am leaving the logs where they are. It is good returned to the earth, and a great place for bugs to get food; but I like things a little tidy so I make giant snags with all the branches I pick up or cut away from the trail, piling them up in spots where they can return as nourishment to the earth but also create nice hiding places for small creatures. I don’t make a pile or snag on what looks like it might be a trail. It’s not a human trail, but someone else; deer, bear or fox. I can see a definite footpath, but barely. And sure, they could go around, but isn’t their life difficult enough already? So why add to that.

Trail maintenance in the Catskills reminds me of where the phrase “you are on rocky ground” comes from. A worn trail quickly becomes a stream in heavy rain, washing away the little bit of soil that was there, leaving a literal pile of rocks to walk on. You have to look down, watch where you step. A little like fighting an uphill battle. It’s not just whatever is uphill that you are battling, but also the hill.

I cut down suckers knowing their meristem, hiding just below the bark, will wait until spring and then start dividing cells to form another sapling. I may or may not get to them next year because I might have something else to do or someone else to tend to.

Making The Right Cut - Trail Maintenance

I know how to make a proper pruning cut, why and where. We call a good cut a “cookie” in the business. It is a perfect, clean circle. But sometimes you can’t do a good cut. The branch that needs to go is too close to another to use a pruning saw, or too upright to the main stem to get your loppers in. Then there are the branches, hanging precariously, stuck on another branch above. I called them “dangling participles” because I like the way it sounds—not because I know what it really is. Something about nouns and verbs. I know that a dead branch dangling above the path is not good grammar either.

While tending to trails, it is not really about the end result but the doing that matters. And in the end, the tender and the recipient both benefit.

If you have any questions or anything to add about trail maintenance in the Catskills please comment below. I would love to hear!

Learn more about me Carolle Huber and the inspiring sustainable landscapes that I design here.

Carolle